The most celebrated inscription at the Central Intelligence

Agency'sheadquarters in Langley, Virginia, used to be the biblical

phrase chiseled into marble in the main lobby: "And ye shall know

the truth, and the truth shall make you free." But in recent years,

another text has been the subject of intense scrutiny inside the

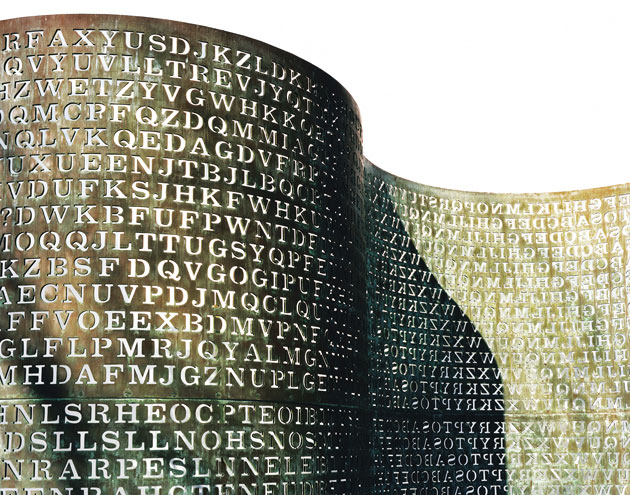

Company and out: 865 characters of seeming gibberish, punched

out of half-inch-thick copper in a courtyard.

It's part of a sculpture called Kryptos, created by DC artist James

Sanborn. He got the commission in 1988, when the CIA was

constructing a new building behind its original headquarters.

The agency wanted an outdoor installation for the area between

the two buildings, so a solicitation went out for a piece of public

art that the general public would never see. Sanborn named his

proposal after the Greek word for hidden. The work is a meditation

on the nature of secrecy and the elusiveness of truth, its message

written entirely in code.

Almost 20 years after its dedication, the text has yet to be fully

deciphered. A bleary-eyed global community of self-styled

cryptanalysts—along with some of the agency's own staffers—has

seen three of its four sections solved, revealing evocative prose

that only makes the puzzle more confusing. Still uncracked are the

97 characters of the fourth part (known as K4 in Kryptos-speak).

And the longer the deadlock continues, the crazier people get.

Whether or not our top spooks intended it, the persistent opaqueness

of Kryptos subversively embodies the nature of the CIA itself—and

serves as a reminder of why secrecy and subterfuge so fascinate us.

"The whole thing is about the power of secrecy," Sanborn tells me

when I visit his studio, a barnlike structure on Jimmy Island in

Chesapeake Bay (population: 2). He is 6'7", bearded, and looks a bit

younger than his 63 years. Looming behind him is his latest work in

progress, a 28-foot-high re-creation of the world's first particle

accelerator, surrounded by some of the original hardware from the

Manhattan Project. The atomic gear fits nicely with the thrust of

Sanborn's oeuvre, which centers on what he calls invisible forces.

With Kryptos, Sanborn has made his strongest statement about what

we don't see and can't know. "He designed a piece that would resonate

with this workforce in particular," says Toni Hiley, who curates the

employees-only CIA museum. Sanborn's ambitious work includes

the 9-foot 11-inch-high main sculpture—an S-shaped wave of copper

with cut-out letters, anchored by an 11-foot column of petrified

wood—and huge pieces of granite abutting a low fountain. And

although most of the installation resides in a space near the CIA

cafeteria, where analysts and spies can enjoy it when they eat

outside, Kryptos extends beyond the courtyard to the other side

of the new building. There, copper plates near the entrance bear

snippets of Morse code, and a naturally magnetized lodestone sits

by a compass rose etched in granite.