Another very important reason for the brightly colored uniforms was that before the invention of smokeless powder, it was very hard to decide which unit someone belonged to by looking at their uniforms; furthermore, even in the best of circumstances, the colors tended to be covered by soot after the shooting had gone on for a while. All the dust that the marching units stirred up had a similar effect.

Smaller, irregular units of scouts in the 18th century were the first to adopt colors in drab shades of brown and green. Major armies retained their color until convinced otherwise. The British in India in 1857 were forced by casualties to dye their red tunics to neutral tones, initially a muddy tan called khaki (from the Urdu word for 'dusty' as the tan matched the local dust). White tropical uniforms were dyed by the simple expedient of soaking them in tea.

This was only a temporary measure. It became standard in Indian service in the 1880s, but it was not until the Second Boer War that, in 1902, the uniforms of the entire British army were standardized on this dun tone for battledress. Other armies, such as the United States, Russia, Italy, and Germany followed suit either with khaki, or with other colors more suitable for their environments.

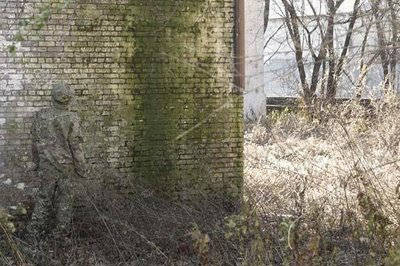

Camouflage netting, natural materials, disruptive color patterns, and paint with special infrared, thermal, and radar qualities have also been used on military vehicles, ships, aircraft, installations and buildings. A striking example of this is the dazzle camouflage used on ships during WW I. Ghillie suits are worn by military special forces units to take camouflage to the next level, combining not just colours, but twigs, leaves and other foliage.